UDL = Universal Design for Learning Principles

The 3 primary principles of UDL are:

Representation: Provides options for acquiring and comprehending information.

(UDL Principle I)

Expression: Provides options to demonstrate learning.

(UDL Principle II)

Engagement: Provides options that tap into learners' interests and provides appropriate challenge to increase engagement. (UDL Principle III)

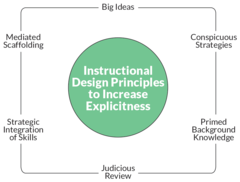

Explicit Instruction

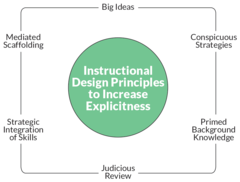

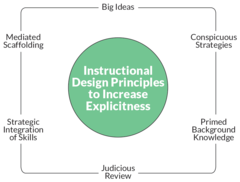

Instruction can be made more explicit and systematic through the use of conspicuous strategies, scaffolding, precise integration of new skills with old skills, priming or supplying background knowledge, and providing a carefully planned review of key concepts and skills.

clearly stated or shown; forthright in expression

Definite, clearly stated

Scaffolding

n education, scaffolding refers to a variety of instructional techniques used to move students progressively toward stronger understanding and, ultimately, greater independence in the learning process. The term itself offers the relevant descriptive metaphor: teachers provide successive levels of temporary support that help students reach higher levels of comprehension and skill acquisition that they would not be able to achieve without assistance. Like physical scaffolding, the supportive strategies are incrementally removed when they are no longer needed, and the teacher gradually shifts more responsibility over the learning process to the student.

Scaffolding is widely considered to be an essential element of effective teaching, and all teachers—to a greater or lesser extent—almost certainly use various forms of instructional scaffolding in their teaching. In addition, scaffolding is often used to bridge learning gaps—i.e., the difference between what students have learned and what they are expected to know and be able to do at a certain point in their education. For example, if students are not at the reading level required to understand a text being taught in a course, the teacher might use instructional scaffolding to incrementally improve their reading ability until they can read the required text independently and without assistance. One of the main goals of scaffolding is to reduce the negative emotions and self-perceptions that students may experience when they get frustrated, intimidated, or discouraged when attempting a difficult task without the assistance, direction, or understanding they need to complete it.

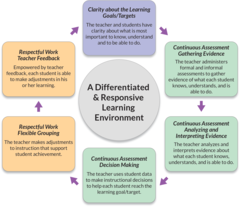

Scaffolding vs. Differentiation

As a general instructional strategy, scaffolding shares many similarities with differentiation, which refers to a wide variety of teaching techniques and lesson adaptations that educators use to instruct a diverse group of students, with diverse learning needs, in the same course, classroom, or learning environment. Because scaffolding and differentiation techniques are used to achieve similar instructional goals—i.e., moving student learning and understanding from where it is to where it needs to be—the two approaches may be blended together in some classrooms to the point of being indistinguishable. That said, the two approaches are distinct in several ways. When teachers scaffold instruction, they typically break up a learning experience, concept, or skill into discrete parts, and then give students the assistance they need to learn each part. For example, teachers may give students an excerpt of a longer text to read, engage them in a discussion of the excerpt to improve their understanding of its purpose, and teach them the vocabulary they need to comprehend the text before assigning them the full reading. Alternatively, when teachers differentiate instruction, they might give some students an entirely different reading (to better match their reading level and ability), give the entire class the option to choose from among several texts (so each student can pick the one that interests them most), or give the class several options for completing a related assignment (for example, the students might be allowed to write a traditional essay, draw an illustrated essay in comic-style form, create a slideshow "essay" with text and images, or deliver an oral presentation).

The following examples will serve to illustrate a few common scaffolding strategies:

The teacher gives students a simplified version of a lesson, assignment, or reading, and then gradually increases the complexity, difficulty, or sophistication over time. To achieve the goals of a particular lesson, the teacher may break up the lesson into a series of mini-lessons that progressively move students toward stronger understanding. For example, a challenging algebra problem may be broken up into several parts that are taught successively. Between each mini-lesson, the teacher checks to see if students have understood the concept, gives them time to practice the equations, and explains how the math skills they are learning will help them solve the more challenging problem (questioning students to check for understanding and giving them time to practice are two common scaffolding strategies). In some cases, the term guided practice may be used to describe this general technique.

The teacher describes or illustrates a concept, problem, or process in multiple ways to ensure understanding. A teacher may orally describe a concept to students, use a slideshow with visual aids such as images and graphics to further explain the idea, ask several students to illustrate the concept on the blackboard, and then provide the students with a reading and writing task that asks them articulate the concept in their own words. This strategy addresses the multiple ways in which students learn—e.g., visually, orally, kinesthetically, etc.—and increases the likelihood that students will understand the concept being taught.

Students are given an exemplar or model of an assignment they will be asked to complete. The teacher describes the exemplar assignment's features and why the specific elements represent high-quality work. The model provides students with a concrete example of the learning goals they are expected to achieve or the product they are expected to produce. Similarly, a teacher may also model a process—for example, a multistep science experiment—so that students can see how it is done before they are asked to do it themselves (teachers may also ask a student to model a process for her classmates).

Students are given a vocabulary lesson before they read a difficult text. The teacher reviews the words most likely to give students trouble, using metaphors, analogies, word-image associations, and other strategies to help students understand the meaning of the most difficult words they will encounter in the text. When the students then read the assignment, they will have greater confidence in their reading ability, be more interested in the content, and be more likely to comprehend and remember what they have read.

The teacher clearly describes the purpose of a learning activity, the directions students need to follow, and the learning goals they are expected to achieve. The teacher may give students a handout with step-by-step instructions they should follow, or provide the scoring guide or rubric that will be used to evaluate and grade their work. When students know the reason why they are being asked to complete an assignment, and what they will specifically be graded on, they are more likely to understand its importance and be motivated to achieve the learning goals of the assignment. Similarly, if students clearly understand the process they need to follow, they are less likely to experience frustration or give up because they haven't fully understood what they are expected to do.

The teacher explicitly describes how the new lesson builds on the knowledge and skills students were taught in a previous lesson. By connecting a new lesson to a lesson the students previously completed, the teacher shows students how the concepts and skills they already learned will help them with the new assignment or project (teachers may describe this general strategy as "building on prior knowledge" or "connecting to prior knowledge"). Similarly, the teacher may also make explicit connections between the lesson and the personal interests and experiences of the students as a way to increase understanding or engagement in the learning process. For example, a history teacher may reference a field trip to a museum during which students learned about a particular artifact related to the lesson at hand. For a more detailed discussion, see relevance.

http://edglossary.org/scaffolding/

Big Ideas

Big Ideas are concepts and principles that facilitate the most efficient and broadest acquisition of knowledge across a range of examples. Big Ideas are what all students should know, understand, and be able to do. More important information should be taught more thoroughly than less important information. Since students with disabilities often need to catch up with their peers and time is limited, big concepts should be the instructional anchors.

conspicuous strategy is a systematic sequence of teaching events and teacher actions that make explicit the steps in learning. They are made conspicuous by the use of visual maps or models, verbal directions, and full and clear explanations.

Planned

Purposeful

Obvious

Understandable

To make a conspicuous strategy:

describe the strategy,

tell the purpose of the strategy,

model the strategy and explain its use,

provide adequate practice,

monitor and provide feedback,

promote student self-monitoring,

encourage the use of the strategy.

Priming background knowledge= hook

Priming background knowledge readies the learner for successful performance. Accessing students' background information is critical for students with disabilities because it is not uncommon for them to have memory deficits. Priming—using a "hook," reminder, or prompt—can alert the learner to retrieve information.

Strategic integration is closely related to priming background knowledge. However, strategic integration refers to combining knowledge to create new knowledge and depth of understanding, while priming background knowledge emphasizes the prerequisites needed for learning new information.

Strategic integration

Combining knowledge to create new knowledge and depth of understanding,

For new information to be understood and applied, it should be carefully combined with things the learner already knows and understands. The teacher needs to make the critical connections. The goal of strategic integration is the combination of what the student knows with what the student is learning so that the relationship between the two things is clear and results in new knowledge.

Judicious Review

Review should be sufficient to enable a student to perform a task fluently.

Review should be distributed over time.

Review should be cumulative, and the information should be applied and generalized.

Review should be varied.

Review opportunities must be frequent to ensure automatically of the skill or knowledge. They must also be brief, yet repeated over time to ensure that the skill or knowledge is sustained.

Review should be judicious, not haphazard.

Missed Question on Saturday night, May 20, 2017- at 10:24pm.

6. For students with learning difficulties, this is critical to success because it addresses the memory and strategy deficits they bring to certain tasks.

I answered Conspicuous Strategies

For students with learning difficulties, this is critical to success because it addresses the memory and strategy deficits they bring to certain tasks.

Judicious Review

Mediated Scaffolding

Conspicuous Strategies

Primed Background Knowledge

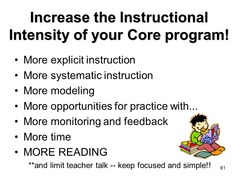

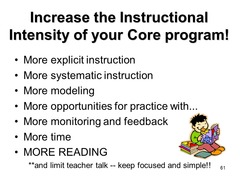

Teacher Delivery Methods to Increase Intensity

Hebrews 12:29- Our God is a consuming fire.

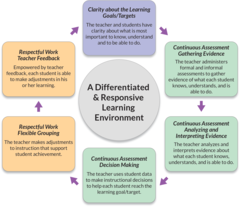

The teacher delivery methods discussed in this section represent the "art of teaching" that can be used to differentiate instruction and make the instruction more intensive. When based on student needs, using these methods effectively keeps students actively engaged and results in more meaningful instruction in less time.

questions missed on pretest of teacher delivery methods on 5/21/17

Teacher delivery pretest was 40%.

Here are the questions I missed 5/21/17

2. Teachers eliminate "down time" by correcting errors in a positive way, providing feedback, and moving to the next thing immediately following student responses.

3. Teachers provide appropriate wait time for students to process their answer but not so much that students lose engagement.

4. Instruction must be precisely focused on what is most critical for students to know, understand, and be able to do, and the work must provide the right amount of challenge.

5. Sufficient practice must be provided within each lesson in order to ensure proficiency.

8. Intensity is increased because the teacher has the opportunity to ensure that students are on-task, engaged, and benefiting from the learning activities.

9. The teacher can make adjustments to instruction by carefully attending to student responses.

Frequent Student Response

When students actively participate in their learning, they achieve greater success. The teacher must elicit student responses several times per minute using highly interactive procedures. Teachers should keep explanations and modeling brief and immediately follow with an opportunity for student response. Having all students respond orally at the same time (i.e., unison response) is one way to keep all members of a small group or whole class actively participating. Unison response is most effective when each student is initiating his or her own response and is not relying on others.

Teacher interacting with group of students

A teacher may use a cue to ensure that higher performers are not leading lower performers. When using a cue, the teacher should model and give brief direction, pause for think time, then cue the response and carefully monitor performance.

Appropriate Pacing

Pacing is the rate of instructional presentations and response solicitations.

When tasks are presented at a brisk pace, students are more likely to be engaged, behavior problems may be minimized, and more practice opportunities are available.

Pace is influenced by task complexity, newness of the task, and student differences.

The real foundation of appropriate pacing is to be very familiar with the teaching material. The teacher must know what is coming next without having to read the teacher's manual or practice book.

It is important for teachers not to rush students. Provide wait time for students to process their answer.

eachers should avoid wasting academic time by having students "guess." Teachers should always provide a model if the material is new. Teachers should provide a "teacher lead" (i.e., do it with the students), if needed. The "teacher lead" should be continued until the students are firm in their knowledge and can answer independently.

A real key to lively pacing is to eliminate "down time" after the student (or students) makes a response. As soon as students respond, a teacher should correct errors positively, provide feedback, and move to the next thing.

Teachers need to be prepared to use "pause" and "punch." Provide more "pause" if the requested response is on new material or is more difficult. "Punch" essential or important information with voice and body language.

Pacing should be fast enough to keep students attending but not so fast that students need to guess.

Adequate Time

Adequate Time

Students who are academically behind their peers must learn more in less time therefore it is important to make the most out of the academic time available. The Matthew Effect (Stanovich, 1986) is based on the concept of "the rich get richer and the poor get poorer." The translation for teachers is that students with a solid foundation of skills do better and learn more because they are able to use these skills to build upon to learn new skills. For example, students who read well tend to spend much more time reading than those who struggle at it and the increased time spent reading makes them increasingly proficient at reading and other related skills.

Just increasing instructional time is not the answer. Instruction must be precisely focused on what is most critical for students to know, understand, and be able to do. When time is increased, it must be academic learning time where students are successfully engaged in academic tasks at the appropriate level of challenge. This means that the work is providing the right amount of stretch. The work cannot be too easy or nothing will be learned, yet not so difficult that students are frustrated or confused. Sufficient practice must be provided within each lesson in order to ensure proficiency. Ongoing informal and formal assessment can be used to determine how to focus the instruction and better align the instruction to individual learner needs.

Matthew Effect

based on the concept of "the rich get richer and the poor get poorer." The translation for teachers is that students with a solid foundation of skills do better and learn more because they are able to use these skills to build upon to learn new skills. For example, students who read well tend to spend much more time reading than those who struggle at it and the increased time spent reading makes them increasingly proficient at reading and other related skills.

Positive Immediate Corrections and Feedback

Model ME

Model

Purpose: Demonstration

Verbal cue:

"My Turn"

Response:

Teacher

Positive Immediate Corrections and Feedback

Lead WE

Lead

Purpose: Controlled Practice to Change Behavior

Verbal cue:

"Do it with me"

Response:

Teacher and children

Positive Immediate Corrections and Feedback

Test THEY

Test

Purpose: Evaluate Response

Verbal cue:

"Your turn, all by yourselves"

Response:

Children only

Positive Immediate Corrections and Feedback

RE-Test YOU

Retest

Purpose: Evaluate entire task

Verbal cue:

"Let's begin again"

Response:

Children only

Teachers must communicate positive expectations to students, especially students with disabilities. Expectations must remain high for these students. Teachers can monitor their feedback to ensure that they are regularly communicating the belief that these students can learn and will succeed.

Small Group Instruction

During small group instruction students should ideally be seated in a semicircle facing the teacher. The teacher should face the small group while looking out over the whole class. More distractible or less-ready students should be placed in the middle of the semicircle closest to the teacher, within easy range of eye contact. This allows teachers to increase intensity by ensuring that students are on-task and engaged in instruction.

Precise Monitoring of Frequent Student Response

When working with students with disabilities, the importance of precise monitoring cannot be overemphasized. It is a prerequisite for efficient instruction. The sooner a teacher detects student errors or confusion, the easier it is to correct misunderstandings. Conversely, if a student with a disability is allowed to practice a skill incorrectly it often makes the remediation process more difficult.

Precise monitoring involves watching and listening to student responses. Every response is a potential source of assessment. Based on student responses, adjustments can and should be made during instruction.

Teacher watching over two students (5-7) working on assignments

If students are answering with unison response, the teacher may not be able to see the fact of every student for every response but he or she should systematically watch each student, with the primary focus being on students of most concern. At times, teachers can also have students answer chorally by pairs. This still keeps a high percentage of students engaged and allows the teacher to better monitor responses. Always follow choral response with individual turns to ensure that each student is at proficiency on the material being taught.