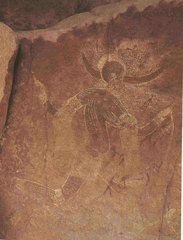

Apollo 11 Stones

Nambia. c. 25000-25300 B.C.E. Charcoal on stone

1. 7 painted stone slabs of brown-grey quartzite, depicting a variety of animals painted in charcoal, ochre, and white. The images are not easily identifiable to species level, but have been interpreted variously as felines. One of them in particular has been observed to be either a zebra, giraffe, or ostrich, demonstrating the ambiguous nature of the depictions. (1-2b)

2. The animal, which may be some sort of supernatural creature, suggests a complex system of shamanistic belief (someone who interacts with a spirit world). Apollo 11 then becomes a site of ritual significance. (1-2f)

3. The Apollo 11 stones are the oldest discovered representational art in Africa, but it is now well-established, through genetic and fossil evidence, that homo sapiens developed in Africa more than 100,000 years ago. (1-2b)

4. The geometric images are painted on stone rather than the inside of a cave. (1-1b)

Great Hall of Bulls

Lascaux, France. Paleolithic Europe. 15000-13000 B.C.E. Rock Painting

1. The caves in which the cave paintings were painted in were not actually where the people lived because they led migratory lifestyles following animal herds.

2. These cave paintings could be interpreted as giving the people "hunting magic" that would provide them with a successful hunt.

3. Some believe they tell stories about certain hunts and give advice/tips. Others believe that the paintings are animal worship or shamanism.

4. The paintings were painted in dark caves using lamps, charcoal, iron ores, plants, colors made with animal fat.

Camelid sacrum in the shape of a canine

Tequixquiac, central Mexico. 14000-7000 B.C.E. Bone.

1. A camelid is an extinct animal from the same family as camels, llamas, and alpacas. A sacrum is a bone at the base of the spine and was considered sacred in many prehistoric Mesoamerican cultures (sacrum in Latin is "sacred bone").

2. The camelid sacrum is thought to have been used for ritualistic practices surrounding fertility and reproduction.

3. The camelid was a source of nutrition for the people in the region and they made sure not let any of the animal go to waste. The value of the animal made every part of it important to the people for different purposes.

4. There is not much information known about the object (if the holes were man-made or occurred while the sacrum was buried, what the definite purpose was for it)

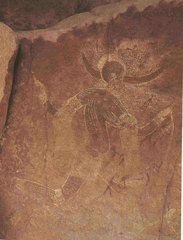

Running horned women

Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria. 6000-4000 B.C.E. Pigment on rock.

1. There are more than 15,000 rock paintings and engravings in Tassili. The art depicts herds of cattle and large wild animals such as giraffe and elephant, as well as human activities such as hunting and dancing. (1-2B)

2. Although the styles and subjects of north African rock art vary, the images usually depict both wild and domestic animals and human figures who are adorned with recognizable clothes and weapons. (1-2E)

3. Composite view of the body. The dots may reflect body paint applied for ritual. The entire site was most likely painted by different groups of people over time. (1-2B)

4. The area was once grasslands but climate change turned it into a desert. (1-1A)

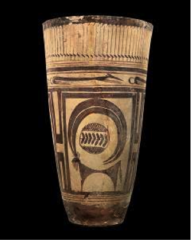

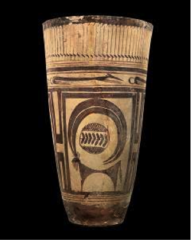

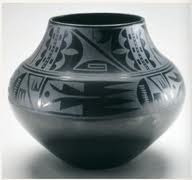

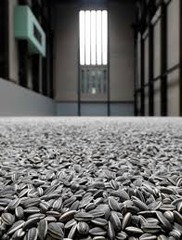

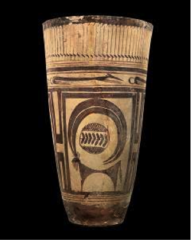

Bushel with ibex motifs

Susan, Iran. 4200-3500 B.C.E. Painted terra cotta.

1. This beaker was discovered under a temple mound that possibly belonged to King David of the Old Testament. It is considered prehistoric (before the rise of Mesopotamian city-states) and many like it were found buried in cemeteries along the fertile river valley in Susa.

2. This beaker is decorated with numerous animal forms such as a mountain goat, dogs, and birds. The geometric patterns that adorn the clay are stylized and very detailed. Included is a "stitching" pattern whose significance is unknown.

3. There are no records of written language or belief system, perhaps this figures are symbols for fertility which would have been greatly important to the people of this time.

4. Although some scholars argue this was made on a small wheel, most agree that it is in fact made and painted by hand. The careful attention to detail and geometric elements of the figures embody the shape of the pot as seen in the mountain goat's round horns and the elongation of the dogs and birds above.

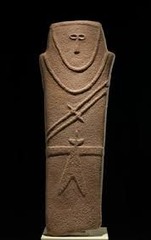

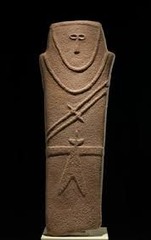

Anthropomorphic stele

Arabian Peninsula. Fourth millennium B.C.E. Sandstone.

1. The stele was found in Saudi Arabia, an area with extensive trade routes, and is one of the earliest works from Arabia.

2. It is thought to be associated with religious or burial practices, and was probably used as a grave marker.

3. Anthropomorphic is a term to describe something that resembles a human. This figure is abstract, but clearly human. The broad shoulders suggest strength, and the rectangular figure signifies that this was is a man.

4. It was created by carving sandstone with a harder type of rock.

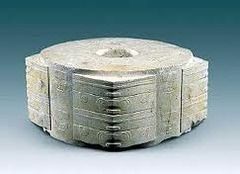

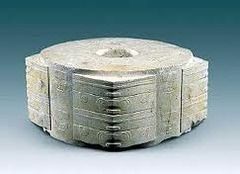

Jade cong

Liangzhu, China. 3300-2200 B.C.E. Carved jade.

The Cong represents power, our relationship with nature, the spiritual world, or what happens after death.

Congs were considered a luxury good for the rich, and found next to their graves.

The circle center represents the afterlife.

The Cong has half human/half animal figure located on it, on the side created out of circles and lines connected together.

Carved by rubbing course sand against the Jade.

Stonehenge

Wiltshire, U.K. Neolithic Europe. c. 2500-1600 B.C.E. Sandstone

Experts describe the site as a very accurate solar calendar.

One bluestone placed outside of the circle is said to be where the sun rose on the summer solstice if one were standing in the center of the henge.

Its creation was a great feat; the stones weigh up to 50 tons.

Also could've been used for ceremonies or rituals, but during the second phase of its construction, it was used for burial.

The Ambum Stone

Ambum Valley, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea. c. 1500 B.C.E. Greywacke

Tlatilco female figurine

Central Mexico, site of Tlatico. 1200-900 B.C.E. Ceramic

1. These objects have two faces with a narrow waist and broad hips. There is a great variety and were often buried with people.

2. The use of two face design features two faces that are sometimes combined and sometimes distinct. This is thought to relate to duality but the lack of a written record means that the reflection of birth, life, and death cannot be confirmed.

3. They often show scene of daily life that are not typically depicted in later art due to the intimacy of the activities.

4. Despite the fact that the clay figures are from the Valley of Mexico around 3,000 years ago, they are not influenced by the Olmec civilization.

5.The figures are mostly of women with few details on the hands of feet. The figures with the two heads or male figures are less common and the male figures are often in the nude.

1. The Tlatilco Female Figurine was a female ceramic figure. Ceramics were widespread for only a few centuries before the Tlatilco figurines. (1.1B,1.2C)

2. Motifs of maize, ducks, and fish are found on the ceramics. The makers of these figurines lived in farming villages. The inhabitants of Tlatilco grew maize and hunted in the lake to sustain themselves. (1.1B, 1.2B)

3. The figurine emphasizes wide hips, spherical upper thighs, intricate hair, and a pinched waist. The majority of these figurines were female, but when men were depicted as men who wore costumes and masks. The two connected heads of the female express an idea of duality. (1.2E)

4. These figurines were found while excavating graves. Inside the graves, the Tlatilco figurines were found in large quantities, suggesting a religious significance to them. (1.2B)

5. The Tlatilco Female Figurine and others like it were made exclusively by hand, without the use of molds. They were made by pinching clay and shaping it by hand. The details were created by a sharp instrument that cut linear markings into the wet clay. (1.2D)

Terra Cotta Fragment

Lapita. Solomon Islands, Reef Islands. 1000 B.C.E. Terra cotta (incised)

1) Lapita art is best known for its cermamics, featuring intricate, repeating geometric patterns that occasionally featured anthropomorphic figures.

2) These patterns were incised onto the wet clay with a stamp before getting fired, stamps were used in conjunction with each other to create unique intricate designs.

3) Many Lapita ceramics were found in large vessels, supposedly pots or cooking utensils, or used to store food.

4) The term Lapita refers to an ancient Pacific culture that archaeologists believe to be the common ancestor of the contemporary cultures of Polynesia, Micronesia, and some areas of Melanesia.

5) Beginning around 1500 B.C., Lapita peoples began to spread eastward through the islands of Melanesia and into the remote archipelagos of the central and eastern Pacific

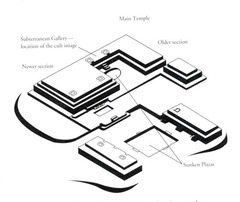

White Temple and its Zuggurat

Uruk (modern Warka, Iraq). Sumerian. c. 35000-3000 B.C.E. Mud Brick.

- A Ziggurat served as a mountain for the gods. It was raised so that the gods wouldn't have to come all the way down to earth - worshipers and priests would meet them halfway.

- Worshipers and processions would approach the temple through bent-axis approach. This suggests approaching a god should be difficult/meditative. This also created opportunity for a parade and created a social hierarchy. For example, the questions were raised: Who gets to go on the platform? Who gets to go in the temple?

- Ziggurats served as the center of city life. They were the visual focal points of the city were visible over the defensive walls of the city. This references both the power of the city and the theocratic political system (a god(s) are recognized as ruler(s))

- Ziggurats were made from mud brick because stone was rare. It took 1500 laborers working long hours for 5 years to build it. Religious belief probably inspired the participation in its construction, but there was forced/slave labor used.

Palette of King Narmer

Pre-dynastic Egypt. c. 3000-2920 B.C.E Greywacke

1. The palette depicts King Narmer as he is uniting Upper and Lower Egypt. His name appears on both sides of the palette and is so valuable that it has never been permitted to leave the country (2-3)

2. On the front of the palette, Narmer is shown wearing the crown of Lower Egypt (red crown) and looking at the dead bodies of his enemies. In the center there are lions with elongated necks which symbolize unification (would have held the makeup). At the bottom of the front side there is a bull knocking down a fortress. This symbolizes Narmer killing his enemies. (2-3B)

3. On the back of the palette is Narmer wearing bowling-pin shaped crown of Upper Egypt (white crown). The king's protector, Horus, is also pictured holding a rope and a papyrus plant around a man's head. These are symbols of Lower Egypt. (2-2A)

4. The palette was used to prepare eye makeup which was used to protects their eyes from the sun. It was probably commemorative or ceremonial. (2-2)

1. This palette is divided into registers, to divide the subject into different scenes and show the importance of certain components of the scene. The pharaoh is shown much larger than all other figures, and represented in composite view. This method of portraying bodies was meant to give the viewer the most information possible about the subject, and was also based in the idea that you had to represent all parts of a figure for the person to be complete in the next world. (2-2.a, 2-3)

2. The pharaoh is much larger than all other figures and is also shown in an idealized form with broad shoulders, small hips and waist, and a muscular form. His enemies are shown trampled under his feet or beheaded. On the top of this piece there is a cartouche, or a place to put the pharaoh's god name after his death. (2-3.b)

3. This piece was made to celebrate the success of the pharaoh in uniting upper and lower Egypt into one kingdom. Cats with long necks that bend like serpents represent the union of Egypt as one of the animals wears the crown of upper Egypt and the other one of lower Egypt. The pharaoh wears a crown combining the two styles. (2-1)

4. The goddess mother of the pharaohs is present to show the divinity of the pharaoh. The god Horus- ruler of the earth, is also present to demonstrate that order on earth, or ma'at, is brought by the pharaoh's divinity and his connection to Horus. (2-2)

Statue of Votive figures from the Square Temple at Eshnunna

Sumerian. c. 2700 B.C.E. Gypsum inland with shell and black limestone

1. The statues were found beneath the floor of a Sumerian temple, the Square Temple at Eshnunna, modern Tell Asmar, Iraq. Essential Knowledge 2-1a

2. The statues of votive figures are of different heights, denoting hierarchy of scale. The tallest and largest figure held the highest importance. Essential Knowledge 2-2a.

3. Votive figures represent mortals, placed in a temple and praying (possibly to the god Abu), and stood continually in prayer attentive to god in place of people of elite class. Inscribed on the back is "It offers prayers". Enduring Understanding 2-1

4. The bodies of the figures are stylistic, with their pinkies in a spiral, chin a wedge shape, and ear a double volute. Essential Knowledge 2-2a

5. The male figures have a bare upper chest, wear a skirt from the waist down, have a flowing beard in rippling patterns, and wear a belt. The females are shown with their dress draped over one shoulder. Essential Knowledge 2-1a.

![Seated Scribe

Saqqara, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynastic. c. 2620-2500 B.C.E. Painted limestone.

1. It represents a figure of a seated scribe at work. The sculpture was discovered at Saqqara, north of the alley of sphinxes leading to the Serapeum of Saqqara, in 1850 and dated to the period of the Old Kingdom, from either the 5th Dynasty, c. 2450-2325 BC or 4th Dynasty, 2620-2500 BCE. It is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

2. The scribe has a soft and slightly overweight body, suggesting he is well off and does not need to do any sort of physical labor. He sits in a cross-legged position that would have been his normal posture at work. His facial expression is alert and attentive, gazing out to the viewer as though he is waiting for them to start speaking.

3. The scribe has a soft and slightly overweight body, suggesting he is well off and does not need to do any sort of physical labor. He sits in a cross-legged position that would have been his normal posture at work. His facial expression is alert and attentive, gazing out to the viewer as though he is waiting for them to start speaking.

4. The Seated Scribe was made around 2450-2325 BCE, it was discovered near a tomb made for an official named Kai and is sculpted from limestone.[1] Many pharaohs and high-ranking officials would have their servants depicted in some form of image or sculpture so that when they went to the afterlife they would able to utilize their skills to help them in their second life. Seated Scribe

Saqqara, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynastic. c. 2620-2500 B.C.E. Painted limestone.

1. It represents a figure of a seated scribe at work. The sculpture was discovered at Saqqara, north of the alley of sphinxes leading to the Serapeum of Saqqara, in 1850 and dated to the period of the Old Kingdom, from either the 5th Dynasty, c. 2450-2325 BC or 4th Dynasty, 2620-2500 BCE. It is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

2. The scribe has a soft and slightly overweight body, suggesting he is well off and does not need to do any sort of physical labor. He sits in a cross-legged position that would have been his normal posture at work. His facial expression is alert and attentive, gazing out to the viewer as though he is waiting for them to start speaking.

3. The scribe has a soft and slightly overweight body, suggesting he is well off and does not need to do any sort of physical labor. He sits in a cross-legged position that would have been his normal posture at work. His facial expression is alert and attentive, gazing out to the viewer as though he is waiting for them to start speaking.

4. The Seated Scribe was made around 2450-2325 BCE, it was discovered near a tomb made for an official named Kai and is sculpted from limestone.[1] Many pharaohs and high-ranking officials would have their servants depicted in some form of image or sculpture so that when they went to the afterlife they would able to utilize their skills to help them in their second life.](https://studytiger.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/seated-scribesaqqara-egypt-old-kingdom-fourth-dynastic-c-2620-2500-b-c-e-painted-limestone-1-it-represents-a-figure-of-a-seated-scribe-at-work-the-sculpture-was-discovered-at-saqqara-north.jpg)

Seated Scribe

Saqqara, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynastic. c. 2620-2500 B.C.E. Painted limestone.

1. It represents a figure of a seated scribe at work. The sculpture was discovered at Saqqara, north of the alley of sphinxes leading to the Serapeum of Saqqara, in 1850 and dated to the period of the Old Kingdom, from either the 5th Dynasty, c. 2450-2325 BC or 4th Dynasty, 2620-2500 BCE. It is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

2. The scribe has a soft and slightly overweight body, suggesting he is well off and does not need to do any sort of physical labor. He sits in a cross-legged position that would have been his normal posture at work. His facial expression is alert and attentive, gazing out to the viewer as though he is waiting for them to start speaking.

3. The scribe has a soft and slightly overweight body, suggesting he is well off and does not need to do any sort of physical labor. He sits in a cross-legged position that would have been his normal posture at work. His facial expression is alert and attentive, gazing out to the viewer as though he is waiting for them to start speaking.

4. The Seated Scribe was made around 2450-2325 BCE, it was discovered near a tomb made for an official named Kai and is sculpted from limestone.[1] Many pharaohs and high-ranking officials would have their servants depicted in some form of image or sculpture so that when they went to the afterlife they would able to utilize their skills to help them in their second life.

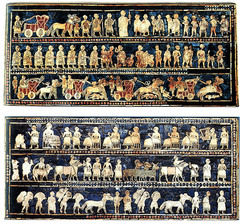

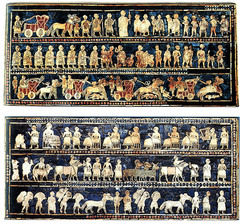

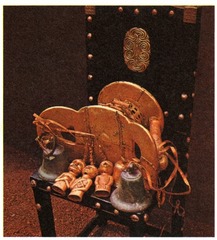

Standard of Ur from the royal tombs

Summerian. c. 26000-24000 B.C.E. Wood inlaid with shell, lapis, lazuli, and red limestone.

1. Found in one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, this piece shows the general representation of power to the Egyptians.

2. (Essential Knowledge 2-1A) Usually the art of the ancient Near East is associated with power because many powerful city-states and cultural power were rising, which was seen specifically in this work.

3. Read from bottom to top, the two main panels depict "war" and "peace".

4. The "war" panel shows one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army at war with a man held captive.

5. The "peace" panel depicts animals and other goods brought in procession to a banquet which includes the same successful priest-king as the "war" panel.

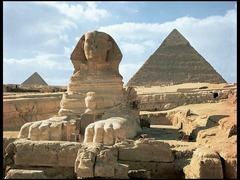

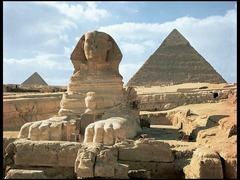

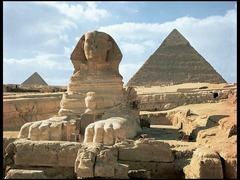

Great Pyramids (Menkaura, Khafre, Khufu) and Great Sphinx

Giza, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynasty. c. 2550-2490 B.C.E. Cut limestone.

1. The three great pyramids were grave sites for three rulers (Khufu, Menkaure, Kharfe) with mortuary temples attached for offerings to the deceased pharaohs. The pyramid was considered a place of regeneration for the ruler.

2. The pyramids are guarded by a great sphinx which has a heard of a human and body of a lion. It is carved in situ from a huge rock to symbolize the sun god. Cats are also royal animals in Egypt which is why it is in front of royalty.

3. They were made of limestone and all the pyramids tips (ben-bens) were solar reference to the sun god. The sun rays were a ramp to climb to the sky.

4. Khufu's pyramid was the largest and he had a ton of boats in his tomb so he could transport to places. Kharfe's pyramid was the middle size and the great sphinx was directly outside of it. Menkaure's pyramid is the smallest of the three and the sculpture of King Menkaure and his queen is found inside.

The code of Hammurabi

Babylon (modern Iran). Susain. c. 1792-1750 B.C.E. Basalt.

Temple of Amun-re and Hypostyle Hall

Karnark, near Luxor, Egypt. New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties. Temple: c. 1550 B.C.E.; hall: c. 1250 B.C.E. Cut sandstone and mud brick.

1. This is a massive temple complex that was the principal religious center of the god Amun-Re in Thebes during the New Kingdom. It held not only the main precinct to the god Amun-Re, but also the precincts of the gods Mut and Montu. (2-2b)

2. One of the greatest architectural marvels is the hypostyle hall. Like most of the temple decoration, the hall would have been brightly painted. With the center of the hall taller than the spaces on either side, the Egyptians allowed for clerestory lighting. (2-3a)

3. Not many ancient Egyptians would have had access to this hall. One would enter the complex through a massive sloped pylon gateway into a peristyle courtyard. The further into the hypostyle hall, the more restricted the access became. (2-3b)

4. The columns in the hall are large, and tightly packed together, admitting little light into the sanctuary. They are elaborately painted and carved in sunken relief. The tallest columns have papyrus capitals and have a clerestory to allow some light and air into the darkest parts of the temple. (2-3a)

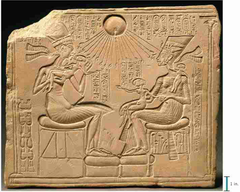

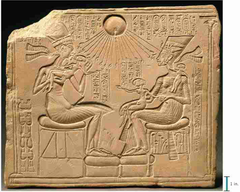

Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Three Daughters

New Kingdom (Amarna), 18th Dynasty. c. 1353-1335 B.C.E. Limestone.

1. This is a (once) painted limestone relief showing Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and their three daughters. Nefertiti's throne has symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt. The carved sun represents the god Aton. (2-1a)

2. Akhenaton changed the state religion from worship of Amun to Aton. The society is now monotheistic, and the art changed to reflect this shift. (2-3a)

3. The shift in state religion created more artist experimentation. Akhenaton and his family are represented in a new canon, characterized by low hanging bellies, slack jaws, smoother curved surfaces, thin arms, epicene bodies and heavy lidded eyes. (2-1a)

4. The royal family has a private relationship with the god Aton, giving them the power. The priests now had no political power. (2-3b)

King Menkaura and Queen

Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynasty. c. 2490-2472 B.C.E. Greywacke

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

Near Luxor, Egypt. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty. c. 1473-1458 B.C.E. Sandstone, partially carved into a rock cliff, and red granite.

1. Hatshepsut herself was the first "female king/pharaoh" of Egypt and the temple has a whole mythology detailing the story of her divine birth (divine births gave pharaohs the right to rule by having received it from the gods).

2. Hatshepsut took power at the beginning of the New Kingdom after a period of disunity in Egypt and believed that returning to the style in which earlier pharaohs had themselves depicted would allow the kingdom to see her as a stable and unifying leader.

3. There is no word in Egyptian for a female ruler because women rarely had that kind of power. The sculptures of Hatshepsut depict her as more masculine with broad shoulders, a flatter chest, and a deemphasized waist.

4. Her nephew/stepson attempted to have all the images of Hatshepsut systematically destroyed after her death. This was originally thought to have been because she had possibly usurped someone of their rightful position as ruler and had forcibly taken away power. A more modern interpretation of this is that there was jealousy surrounding her right to rule by other members of the royal family.

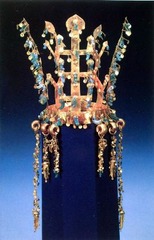

Tutankhamun's Tomb, intermost coffin. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty. c. 1,323 B.C.E. Gold with inlay of enamel and semiprecious stones.

The innermost coffin is painted to look like King Tut in god form.

Gods were though to have skin of gold, bones of silver, and hair of lapis lazuli.

The crook and flail that he holds are the symbols of the king's right to rule.

The goddesses Nekhbet (vulture) and Wadjet (cobra) are inlaid with semiprecious stones, along with Isi and Nephthys.

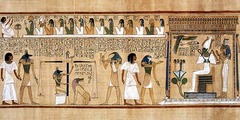

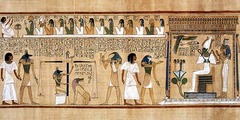

Last judgement of Hu-Nefer, from his tomb

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty. c. 1,275 B.C.E. Painted papyrus scroll

1. This work was originally found in the tomb of Hu-Nefer. Hu-Nefer was a scribe, and would have been considered high status.

2. The illustration comes from the Book of the Dead, which is a collection of spells, prayers, and charms.

3. The scroll shows Anubis, the jackal headed god, leading Hu-Nefer to his judgment. Anubis weighs Hu-Nefer's heart on a scale against the feather of truth, while Thoth, the god of scribes, records the results. A creature that is part crocodile, leopard and hippo sits ready to devour Hu-Nefer's heart if it is not pure. Hu-Nefer's heart is true, and Horus, the falcon headed god, presents him to Osiris, the judge and god of the underworld.

4. The scroll is made of papyrus, which is a paper-like substance that grows in the Nile Delta.

Lamassu from the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin

Neo-Assyrian. c. 720-705 B.C.E. Alabaster

-Guardian figures that protected the citadel (temple & palace)

-Fierce & powerful, symbolizes the king

-Inscriptions in cuneiform articulate the power of the king and damnation of those who don't obey him

-Assyrians were one of the first to create grand arches and entrances (opposite of the Greeks, similar to the Romans) that were more structurally sound since weight is distributed out to surrounding the walls

1. The Lamassu were guardian figures that stood at the gateways to the city and its citadels. It would have been impossible to approach the citadel without seeing them. (2.1A)

2. They were created at the height of Assyrian civilization. They were an expression of the power of the Assyrian king. They are comparable to Sphinxes in the Egyptian tradition. (2.1B)

3. The perspective of the Lamassu is different depending on where someone views it. From the side, the legs appear to be walking with the viewer and is welcoming. From the front, the figure is static and formidable. (2.1)

4. The face of the Lamassu has wavy hair, connected eyebrows, earrings, and an elaborate beard. The wings form a decorative panel which show power and prestige. (2.1)

5. The figure is carved out of a monolithic stone. There are inscriptions that talk about the power of the Assyrian empire. (2.1A)

Athenian agora

Archiac through Hellenistic Greek. 600 B.C.E.-150 C.E. Plan

1) The agora was used in the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic eras as a public place of debate, place of worship, and marketplace, played a central role in the development of the Athenian ideals, and provided a healthy environment where the unique Democratic political system took hold.

2) This democratic society directly chose government officials (you had to be a man and athenian) many of whom stayed in office because they were voted in so many times (Pericles served 15 terms as general)

3) The Agora became the epicenter of athenian life, and hosted many culturally enriching sites.

4) The Stoa is a large hypostyle hall where political discussions took place, a market was held, and civic life was held.

5) Once a year, a great procession would make its way through the agora up to the sacred mount- this celebration was in honor of Athena and traveled up to the parthenon.

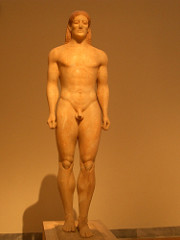

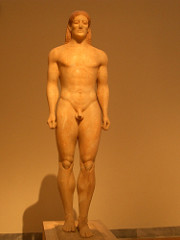

Anavysos Kouros

Archaic Greek. c. 530 B.C.E. Marble with remnants of paint

- "Kouros" statues were idealized statues of young men common throughout Ancient Greece. They were used as grave markers or set up near graves as votive statues or set up outside temples.

- This statue is representative of the development of naturalism and the movement away from abstraction. Greeks elevated the human body and the human mind to the highest status. There was more emphasis on capturing realism than in Egyptian culture. The artist depicts toned muscles, especially in the strong legs and abdomen. It also would have been painted to make it seem more lifelike.

- It is very idealized and follows the Greek Cannon. For the artist, it was seen as a mark of expertise if they would sculpt a human body that actually looked realistic.

- The artist uses heroic nudity to show the figure's self control and physical excellence

- The headdress and left leg in front are similar to those of Egyptian statues, suggesting that the greeks were both influenced and inspired by the Egyptians

Peplos Kore from the Acropolis

Archiac Greek. c. 530 B.C.E. Marble, painted details

1. It is a sculpture of a young female with open eyes, an archaic smile, braided hair, a damaged nose, and a broken left arm. There are also holes in her head which have originally may have held a crown. (2-5B)

2. They were usually created as votives or offerings to goddesses, but this particular sculpture might not be an offering but an actual goddess herself. It might be the goddess Artemis who would have been holding a bow and arrows. (2-4C)

3. There are traces of red paint that are still visible. With a special camera, other bright colors and patterns can be seen. An example of this is her archaic smile which is an unnatural smile that is meant to show a sense of well-being. (2-4C)

4. The sculpture is done in marble. It was painted using the encaustic technique which is the mixing of colored pigments with wax so the color bonds well to the heated sculpture. (2-5B)

Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Etruscan. c. 520 B.C.E. Terracotta

1. The outside is a portrait of the married couple, whose ashes were placed inside. The couple has a symbolic relationship; the man has a protective arm around the woman, while the woman is seen feeding the man. This reflects the high standing women had in Etruscan society. Essential Knowledge 2-5a

2. Although the Etruscan's have many influences from the Greeks, the joint sarcophagus is unique to Etruscan burial because the Greeks were buried individually, separate from their partners. Tombs were also not apparent in burials of Greeks either. Enduring Understanding 2-4

3. The bodies of the figures are placed at an angle where their legs are forced into an unrealistic L-turn. The bodies have broad shoulders but are shown with little anatomical modeling, as well as emaciated hands. Essential Knowledge 2-4c

4. The couple is seen reclining. There is an ancient tradition of reclining while eating, and their sarcophagus represents a banquet couch, which the couple rests on. Enduring Understanding 2-4

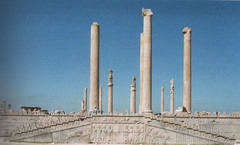

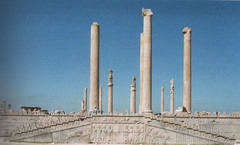

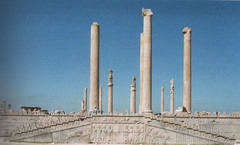

Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes

Persepolis, Iran. Persian. c. 520-465 B.C.E. Limestone

1.Persia was the largest empire the world had seen up to this time. As the first great empire it need an appropriate capital as a grand stage to impress people at home and dignitaries abroad. Persepolis included a massive columned hall used for receptions by the Kings called the Apadana. The audience hall itself is hypostyle in its plan. The audience hall called the Apadana had 36 columns covered by a wooden roof. The audience hall held thousands of people and was used by the kings receptions. Two monumental stairways were adorned with reliefs of the New Year's festival and a procession of representatives of 23 subject nations.

2. The column capitals assumed the form of either twin-headed bulls, eagles or lions, all animals represented royal authority and kingship. The columns had a bell shaped base that is an introverted lotus blossom. Many cultures (i.e, Greeks, Egyptians, Babylonians) are seen to have contributed to the building

3. The monumental stairways that approach the Apadana were adorned with registers of relief sculptures. The north and east stairways are decorated. The theme of that program us one that pays tribute to the Persian king himself as it depicts representatives of 23 subject

nations bearing gifts to the king.

4. The walls of the spaces and stairs leading up to the reception hall were carved with hundreds of figures. The registers of relief sculpture depicted representatives of the 23 subject nations of the Perisan empire bringing valuable gifts as tribute to the king. The sculptures form a processional scene, leading scholars to conclude that the reliefs sculpture capture the scene of actual, annual tribute processions perhaps on the Persian New Year that took place at Persepolis. The two sets of stairway reliefs mirror and complement each other. Each program has a central scene of the enthroned king flanked by his attendants and guards. In the reliefs noblemen wearing elite outfits and military appeal are present. The relief program of the Apadana serve to reinforce and underscore the power of the Persian king and the breadth of his dominion.

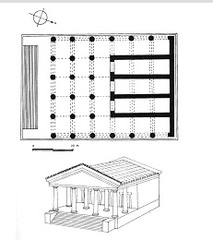

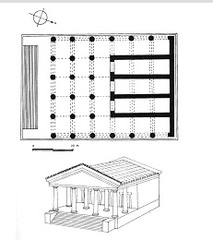

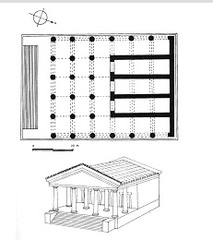

Temple of Minerva and sculpture of Apollo

Master sculptor Vulca. c. 510-500 B.C.E. Original temple of wood, mud brick, or tufa; terra cotta sculpture

1. This Etruscan temple was made out of mud brick with a stone foundation, and the modified doric columns were made out of wood. These materials were less permanent than the materials used by Greek and Roman societies and therefore this structure is no longer in existence. (2-5)

2. Clay statues were displayed on the roof of the temple, portraying a scene of the god Apollo struggling with Heracles for a tripod. These figures are meant to be representative of ideal humans, and are designed to be viewed from a distance. The figures have archaic smiles, and use drapery in contrast to Greek figures which were often nude. (2-4.c)

3. Figures on the roof of the temple are comparable to Greek kouros statues in some ways but show distinct aspects of Etruscan art. None of the figures are nude on the Etruscan temple, but some scholars believe Kouros statues were meant to be depictions of the god Apollo, and the Etruscan art on the roof of this temple depicts Apollo. The Etruscan statues are less realistic due to their placement on a temple roof, and are relatively flat because they were generally only viewed from a frontal perspective. (2-4)

4. This temple differs from Greek temple composition in several ways, including the fact that it has a colonnade only on the front, has exposed beams, and has a much smaller staircase which is also only in the front of the temple. Overall the structure is not as impressive or imposing as Greek or Roman temples. There is a front porch on the temple, and the interior sanctuaries are dedicated to Zeus, Athena, and Hera. (2-4)

Tomb of the Triclinium

Tarquinia, Italy. Etruscan. c. 480-470 B.C.E. Tufa and fresco

1. Funerary Contents in the Etruscan culture tell us the most about their civilization, for example, the elite members performed funerary rituals and we are able to see how they changed based on time and location.

2. The city where this tomb was found was one of the most powerful and important cities in Etruscan times and is specifically known for its painted chamber tombs. The tombs were also made out of subterranean rock. The walls of this tomb reveal important information about funeral processes but also ways of living. For example, we can tell that the Etruscans got much of their wealth from long trading networks where they traded metal and mineral oils.

3. The tombs hold the remains of the person but also grave goods and offerings. This tomb is called the Triclinium tomb because of the fresco painted on the wall of a three-couch dining room. The back wall included a scene of many people enjoying a dinner party, people are eating while reclining (Kline figures). The diners are dressed very well which implies high status. Dancers and music appear all over the walls which show the happy tone and the accompany of games and which was a tradition.

4. The tone of the frescos are happy and festive because it Etruscan Culture they celebrated the dead and sought to share a final meal with the deceased. They also were trying to emphasize the importance of the person who died.

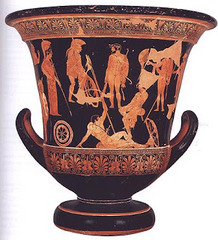

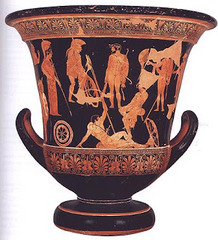

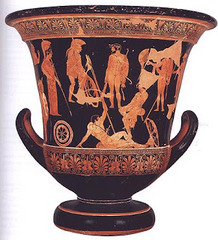

Niobides Krater

Anonymous vase painter of Classical Greece known as the Niobid Painter. c. 460-450 B.C.E. Clay, red-figure technique

1. The Niobid Painter, probably inspired by the large frescoes produced in Athens and Delphi, decorated this exceptional krater with two scenes in which the many figures rise in tiers on lines of ground that evoke an undulating landscape.

2. The main side of the vase shows eleven figures placed at different levels. Only two of them are recognizable: Heracles, in the center, holding his club and bow, with his lion skin over his left arm, and Athena on the left. Around them several warriors are represented in varying poses.

3. Heracles - crowned with laurels, wrinkled and standing on a stepped base almost invisible to the naked eye

4. The B side of the vase illustrates a legend that is rarely represented, and gave the painter his name. Here we see the massacre of the children of Niobe by Apollo and Artemis.

5. The stylistic characteristics of this krater owe much to contemporary sculpture and wall paintings.

Doryphoros

Polykleitos. Original 450-440 B.C.E. Roman copy (marble) of Greek original (bronze)

1. 1. This statue is called "Spear Bearer" (Greek: Doryphoros) because of the empty hand which in Greek times was carrying a spear. He has a closed stance and contrapposto. His left arm and right leg are relaxed and his right arm and left leg are tense. The style of Contrapposto is defined in this piece, because of its ultimate proportions of the human figure.

2. After the Peloponnesian War, sculpters started to turn away from idealistic figures and more to humanized statues. Gods were portrayed extremely detailed and like humans. The fourth century opened up the expressions of emotions through sensuous and languorous statues as well as heads that are as small as 1/8th of the body.

3. Specific to Doryphoros, he has a blocklike solidity, broad shoulders, thick torso, and a muscular body. He was thought to have been placed in a gym in sparta for soldiers as the ultimate human form. It portrays one who is both a warrior and an athlete. He is so great that he turns his eyes away from you, although you admire him. He does not recognize the admiration.

4. Part of the reason that this one statue is so popular and celebrated, is because a majority of the sculptures from the fourth century were made of bronze. During war, bronze was the main metal used for weapons, so the Greeks would melt down their statues to use for weapons. This is the reason that this statue like most others, is in a marble copy. So that we can still observe the beauty of Greek art.

Acropolis

Athens, Greece. Iktinos and Kallikrates. c. 447-410 B.C.E. Marble

1. There was an older temple to Athena in that same area that was destroyed when the Persians invaded. The Persians destroyed and burned down the temple and the Athenians took a vow to never rebuild it but a generation later they decided to rebuild the Athenian temple. The Delian League, a tax money fund, may have been what paid for it. It was a sacred area that was dedicated to Athena. Eventually housed the city-state tax money, storehouse, and treasury, full of valuable things and functioned as a symbol of the city's wealth and power and point of awe.

2. Mathematics and building skills and search for perfect harmony and balance were all important to the Greeks so the Parthenon demonstrates all these things. Its architectural perfection is an illusion based on subtle distortions that correct the imperfections of human sight. For example, the columns bulge out fractions of an inch towards the center in order to create the illusion of a perfectly straight column. The Parthenon is a doric temple with ionic elements. There are massive column outside with shallow, broad flutes going directly down and a simple little flair at the top and four ionic columns in the west end of the temple. The triglyphs and metopes were covered in sculptures depicting stories or Greeks battling against enemies. There was a frieze inside the porch depicting a procession of the people of Athens towards the Parthenon (a historical representation rather than mythological or religious) that ran along the outside of the Temple which was an ionic feature. (2-4c, 2-5b)

3. There are a series of Nikes in the Temple of Athena Nike, the most famous sculpture is Nike Adjusting her Sandal. The sculpture shows her possibly taking her sandal off as she is in a sacred space and she is depicted with eroticism through her clothes and the way that they drape her body which was a big deal. The emphasis on drapery was a stylistically very much a part of the Classical period. There was also an emphasis on her body and form seeming natural, relaxed, and imbalanced. (2-4b, 2-5b)

4. The Acropolis represents the birth of democracy as there was a shift in government in the 5th century that made it easier for the Greek people to participate in their government. Many more governmental buildings are based upon the outward architecture of the Parthenon to embody that same sense of democracy and its roots. (2-4d)

Grave stele of Hegeso

Attributed to Kallimachos. c. 410 B.C.E. Marble and paint

Winged Victory of Samothrace

Hellenistic Greek. c. 190 B.C.E. Marble

1. This statue has its name because it was found on the island in the north of the Aegean which is called Samothrace. It was found in a sanctuary in the harbor that actually faces the predominant wind that blows off the coast, which seems to be enlivening her drapery. It was probably built to commemorate a navel victory in 190 BCE. (2-4a)

2. She is the goddess of victory and a messenger goddess who spreads the news of victory. (2-5b)

3. This image has an enormous impact on Western art because of the lack of reserved, high classical style. There is voluptuousness and a windswept energy that is full of motion and emotion. This is what the Hellenistic style looked like. She moves in several directions at the same time, is grounded by her legs but strides forward, and her torso lifts up. There is dramatic twist and contrapposto of the torso. (2-4b & 2-4d)

4. The statue is a reminder of the sculptures from the Parthenon frieze, but instead of the quiet, relaxed attitude of the gods on Mount Olympus, there is energy to natural forces that the goddess is responding to. The wet drapery look imitates the water playing on the wet body and shows evidence of invisible wind on her body. (2-4c)

Great Altar of Zeus and Athens at Pergamon

Asia Minor (represents-day Turkey) Hellenistic Greek. c. 175 B.C.E. Marble

The gigantomachy was supposed to represent the Pergamene victory over the guals.

There was a deliberation connections made to Athens because they had already gloriously defeated the Persians and the Parthenon was already a highly regarded monument.

The frieze of Athena battling Alkynoeos is a reference to the Athena from the east pediment of the Parthenon and Zeus is a reference to Poseidon from the west pediment.

The gigantomachy shows that the Greeks had fear, but they could overcome chaos. The battle represented the victory of Greek culture over the unknown, chaotic forces of nature and the military victory over cultures that they thought were chaotic and didn't understand.

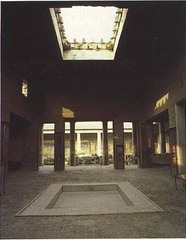

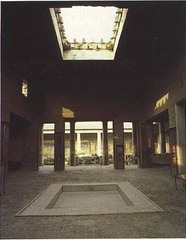

House of Vetti. Pompeii, Italy. Imperial Roman. c. second century B.C.E.; rebuilt c. 62-79 C.E. Cut stone and fresco

1. Serves as representative for Roman townhouses in Pompeii, Italy. They functioned as both domestic space and a business space.

2. Aristocratic families used the domestic space to reflect their social position through the decoration and the business space to continue expanding their wealth. The Roman Republic was based on a patron-client relationship and the setup of the homes was meant to reflect this by having aristocrats receive clients in a domus (townhouse owned by the wealthy).

3. Freedmen (former slaves) also often occupied these homes and used them as a way to advance their social standing after leaving slavery.

4. Domestic decoration in the House of Vettii as well as other domus homes was meant to reflect the wealth and the education of the aristocratic class by having reproductions of famous artworks or having artwork similar to famous pieces.

Alexander Mosaic from the House of Faun, Pompeii

Republican Roman. c. 100 B.C.E. Mosaic

1. The Alexander Mosaic was the floor of a house in Pompeii, in which it was pasted into cement. A million and a half pieces of colored pebbles make up the mosaic. The mosaic was made during the Roman Republic. (2.4A)

2. The mosaic is based on an ancient Greek painting that was lost in time. Literature tells art historians that the Greek wall painting was immensely beautiful, but the mosaic is the closest there is to the original. The Roman copy of a Greek painting shows the regard that the Romans had for Greek art. (2.4C, 2.5A)

3. The mosaic depicts the ruler of Persia, King Darius, fleeing from Alexander the Great's Greek army. King Darius looks terrified and is begging Alexander to spare his soldiers. This speaks to the power of the Greek Empire under Alexander's reign. (2.1A, 2.5B)

4. There is incredible realism in the figures of the mosaic. The artist uses light and dark to create 3D forms. The anatomy of the bodies is realistic, and the horses are foreshortened to create perspective. (2.4C)

Seated boxer

Hellenistic Greek. c. 100 B.C.E. Bronze

1. The Greeks were employed by the Romans to create works of art even after they were conquered by them.

2. This figure is less idealized than traditional Greek works that showcased contrapposto.

3. 2-4C The was a Greek Hellenistic statue (Hellenistic refers to the period after Alexander the Great) and was particularly representative of the Hellenistic period as it explored the different aspects of human form and condition explored through art.

4. 2-4C The Boxer, unlike previous statues, is not a perfect representation of a human body or condition, in fact there is an emphasis on this Boxer's defeat. His posture is slumped, and his ear have been beaten badly, the ties of leather around his knuckles show us that he has been in battle.

5) The blood drops are also indicative of the boxer's defeat, his pained expression and hunched defeat even though he is muscular, energies the viewer with pathos, or, emotionally.

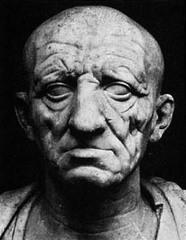

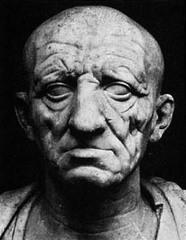

Head of a Roman patrician

Republican Roma. c. 75-50 B.C.E. Marble

- Only patrician (wealthy) families could have these. They would parade them through the streets during the person's funeral as a "death mask".

- The parade was meant to highlight the person's role as a patrician and the busts highlighted the old age of the person (the oldest male of each patrician family would sit in the senate).

- After the parade, the busts would be kept in the family's residence as a reminder of the lineage of ancestors and their everlasting power and wealth.

- Veristic verism was used by the sculptors to depict someone just as ugly as they were (or uglier). This caused the busts to express little vanity and allowed the dead to be remembered as wise, knowledgeable, and having longevity.

1. The bust was created in the style of verisitic verism. In this style, the features of the individual are exaggerated to emphasize their wisdom, experience, and humility. Although features are altered, the ancestor is still easily identifiable.

2. These busts were essentially death masks of important ancestors that were kept and displayed by the family.

3. The masks would have been used in parades at other funerals in order to honor the individual's role as a patrician and portray deceased ancestors.

4. The realistic portrayal of the individual shows the influence of Hellenistic art.

Augustus of Prima Porta

Imperial Roman. Early first century C.E. Marble

1. This represents the ideal view of the Roman emperor. It was used as propaganda and was supposed to communicate Augustus's power and ideology. He shows himself as a military victor and a supporter of Roman religion. (2-4C)

2. The statue stands in a contrapposto pose and he is wearing military regalia. His right arm is outstretched which symbolizes that he is addressing his troops. It has a big similarity to 'Doryphorus'. (2-4C)

3. At his right is a figure of cupid riding a dolphin. The dolphin symbolizes Augustus's victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra which allowed him to become the sole ruler. Cupid symbolizes the fact that Augustus is a descendant of gods. Cupid is the son of Venus and Augustus's father claimed to be a descendant of Venus. (2-5B)

4. The breastplate that the stature is wearing also has a lot of symbolism. Two of the figures are a Roman and a Parthian. The Parthian is returning military standards. This is a reference to a victory of Augustus. On the side there are female personifications of of countries conquered by Augustus. (2-4C)

Colosseum (Flavin Amphitheater)

Rome, Italy. Imperial Roman. 70-80 C.E. Stone and concrete

1. The real name of the Colosseum is the Flavian Amphitheater, named after the Emperor Flavian, who converted the area into a public space from the previous emperor's private lake. It gained the name Colosseum because of its massive size. Essential Knowledge 2-4c

2. Romans were able to build the large structure through use of a concrete core, brick casting, and travertine facing. Also there was interplay of barrel vaults, groin vaults and arches. Essential Knowledge 2-4c

3. The façade contains multiple types of columns from different cultures and time periods. The first story is Tuscan, second floor Ionic, third floor Corinthian, and the top a flattened Corinthian. Each floor was thought of as lighter than the order below. Enduring Understanding 2-4

4. Later in time, especially in the Middle Ages, much of the marble was pulled off the Colosseum and used in other buildings. Enduring Understanding 2-4

5. The area was meant for entertainment, especially wild and dangerous spectacles. Often there were animal hunts and fights, gladiator battles, and naval battles. Enduring Understanding 2-4

Forum of Trajan

Rome, Italy. Apollodorus of Damascus. Forum and markets: 106-112 C.E.; column completed 113 C.E. Brick and concrete (architecture); marble (column)

Pantheon

Imperial Roman. 118-125 C.E. Concrete with stone facing

1.The name implies that it is dedicated to all of the gods (which it was) as there were alcoves to seven of the gods in the rotunda of the temple. (1-4 B)

2. The space is a mix of circular and square motifs wit the square panels of the floor and ceiling coffers contrasting with the roundness of the overall architecture. (1-4 A)

3. The ceiling of the temple was filled with square coffers that may have once help bronze rosettes that were meant to represent stars and simulate the feeling of the heavens via the sky. ( 3-2)

4. The central oculus of the dome is 27 feet across and allows for ventilation and the creation of a moving circle that moves around the structure during the course of the day. This feature further references the connection of the structure to the heavens and the gods. (3-2)

5. The structure was made possible via the Roman invention of concrete. The concrete was heavier towards the bottom of the dome to support the structure and lighter towards the top to allow the height of the dome. This was done by mixing in different materials into the overall concrete mixture. The weight is pressed into the ground via columns that support the structure's weight. (1-2 A)

Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus

Late Imperial Roman. c. 250 C.E. Marble

1. The romans are the good guys and the bad guys are the goths, the romans are portrayed as noble, stern, and serious which is to show importance of battle, heroic, and idealized while their enemies look barbaric, ugly, concerned, and in fear.

2. There is no room to move with dense carpet of figures, there is 2 to 3 layers of figures. As your eyes move down the figures get smaller so that we have a different perspective called organizing perspective.

3. In the center is the obvious hero on his horse opening up his arms. He is calm and composed like a good leader. He doesn't have a helmet which shows he is invincible, all powerful, and needs no protection. Light and dark variations animate the surface.

4.Someone wealthy and powerful owned the sarcophagus because it took a very long time to carve with a very skilled carver. The surface mirrors the chaos of the empire at the time after Augustus which was very unstable so the surface shows chaos which can be linked to the instability of the empire. Turning away from Greek high classical art and becomes less concerned with individuality and the elegance of the human body.

Catacomb of Priscilla

Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 200-400 C.E. Excavated tufa and fresco

1. Unlike Roman mosaics, which are made out of rock, Christian mosaics are often of gold or precious materials and faced with glass. Christian mosaics glimmer with the flickering of mysterious candlelight to create an other worldly effect. Catacombs beneath Rome have 4 million dead and extend about 100 miles. Contains the tomb of seven popes and many early Christians martyrs.

2. The Greek Chapel is named for two Greek inscriptions painted on the right of the niche. The three niches are for the sarcophagi. It is decorated with painting ins the Pompeian style; sketchy painterly brush strokes.

3. Orants Figures: Fresco over the tomb niche set over an arched wall; cemetery of a family vault. The figure is compact ,dark, set off from light background; tensing angular contours; emphatic gestures and stands with arms outstretched in prayer.

4. Good Shepherd Fresco: Restrained portrait of Christ as a good shepherd which is a pastoral motif in ancient art going back to the Greeks. The symbolism of the Good Shepherd is that it rescues individual sinners in his flock that went astray.

Santa Sabina

Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 422-432 C.E. Brick and stone, wood

1. Santa Sabina represents a synthesis of pagan Byzantine culture and an emerging acceptance of Christianity. It was constructed under the emperor Constantine who was privately Christian and baptized on his death bed. Components of the church are clearly borrowed from traditional Roman architecture including the triumphal arch over the altar in this church. This type of arch was traditionally used to commemorate generals or emperors and their victories, but were now being used by the Christian community to celebrate the triumph of the church. (3-1.a)

2. The structure of the church is based on Roman bascilicas to include more interior space for worshipers ar masses, give a sense of imperial authority to God, and incorporate a longitudinal axis in order to place focus on the altar. (3-1.c)

3. The cross shape that came with the use of the basilica structure is clearly symbolic in Christianity, and the transept of the cross shape was where the most prestigious members of the church sat for mass. (3-2.b)

4. The walls in Santa Sabina have very large windows and give a clear sense of light and space. The décor also incorporates columns repurposed from pagan structures. These factors not only give a sense of divinity through the use of lightness and ethereality in the decoration, but also represent a victory of Christianity over Paganism through the repurposing of the columns. (3-2.b)

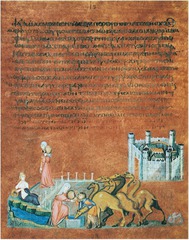

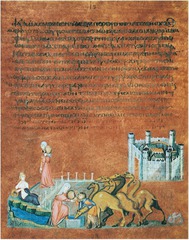

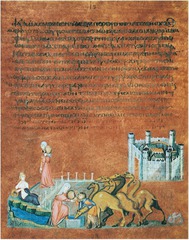

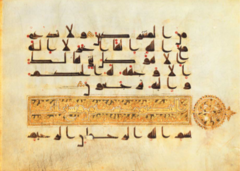

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well and Jacob Wrestling the Angel, from the Vienna Genesis

Early Byzantine Europe. Early sixth century C.E. Illuminated manuscript

1) The creation of religious manuscripts such as this one was a very time consuming process. The pages are purple vellum which is treated animal skin, suggesting a royal institution, and all the writing and illustrations were done by hand using silver script. The care and detail taken with such manuscripts makes them very important and accessible by only the very wealthy. (3-2)

2) The style of the illustration is very classical and shows the training of the artist in Greek and roman tradition. Foreshortening, shadowing to show depth, contrapposto and the roman style of columns and arches on bridge are all examples of classical elements in this piece. (3-1C)

3) The perspective used in this illustration is typical of the Byzantine period but different from the classical linear perspective of the previous period. Here all the figures are the same size regardless of which section of the narrative they are from. Also the perspective on the bridge is unique, the columns that would appear closest to the viewer are smaller than the columns from earlier in the narrative, opposite how they would appear using linear perspective. (3-1B)

4) The illustrations on both of these pages were done to aid the reader in contemplation over the religious stories. One page shows Jacob leading his family and wives and then wrestling with the angel who then blesses him, using a bridge to wrap the scene around in two levels. The other page is also a narrative that has multiple scenes, showing Rebecca assisting Isaac with his camels at the well. (3-2C)

5) The image of Rebecca and Eliezer at the well also demonstrates the shift in art style between the classical period and early medieval art. The nude next to the river is a very classical element, which contrasts with Rebecca's outfit of heavy drapery and simplified clothing, typical of early Christian art. The presence of the walled city, which is a symbolic element is not shown in a spatially accurate way, which is typical of medieval art. (3-1C)

San Vitale

Ravenna, Italy. Early Byzantine Europe. c. 526-547 C.E. Brick, marble, and stone veneer; mosaic

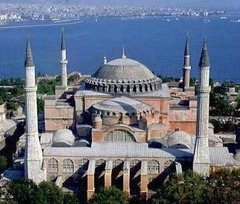

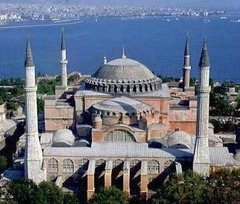

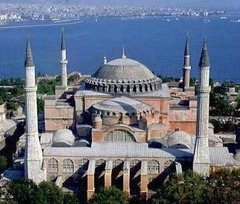

Hagia Sophia

Consantinople (Istanbu). Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. 532-537 C.E. Brick and ceramic elements with stone and mosaic veneer.

1. Constructed during the rule of Emperor Justinian I and serves as a symbol of the entire Byzantine Empire the same way the Pantheon serves as a symbol for classical Greece. Also served as a way for the emperor to assert his power over the people.

2. Inspiration for the columns used in the construction of the building come from the Classical Ionic order but features uniquely Byzantine treatment in the capital of the column.

3. The church has been burned down several times during riots against the emperor and damaged by earthquakes in the region and has had to be repaired because of it's importance to the history of the region (Istanbul, Turkey).

4. Two scholars were hired to figure out how to vault the dome roof of the building: creation of a centrally planned building in a basilica setup. The dome is essentially grounded on a pendentive that takes the load of the dome and distributes the weight on to stone piers and several several smaller half domes.

Merovingian looped fibulae

Early medieval Europe. Mid-sixth century C.E. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones.

A fibula is a pin or brooch used to fasten garments and to show the status of the wearer.

They were made popular by Roman military campaigns.

They have a cross and a fish on them, alluding to Christianity.

Animal imagery was common.

Warriors would wear them to keep their cloaks on, while others would wear it to show status.

Cloisonne and chasing techniques were important to the Frankish people.

Virgin and child between Saints Theodore and George

Early Byzantine Europe. Six or early seventh century C.E. Encastic on wood.

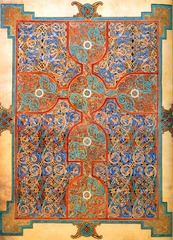

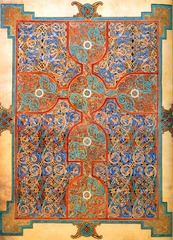

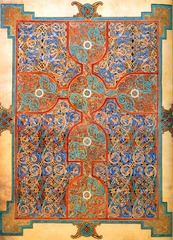

Lindisfarne Gospels: St. Matthew, cross-carpet page; St. Luke portrait page; St Luke incipit page

Early medieval (Hiberno Saxon) Europe. c. 700 C.E. Illuminated manuscript (ink, pigment, and gold)

1. The Lindisfarne Gospels were created by monks who devoted their time to making these books. The depiction of the Gospel writers (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), is comparable to the monks, the writers of these Gospels. (3.1A, 3.2C)

2. They were written in black ink even though at the time, brown ink was more commonly used and was cheaper. Black ink was harder to make, and therefore more expensive, but the monks decided that it enhanced the importance of the gospels. (3.1B)

3. The intricate swirls and designs of the Lindisfarne Gospels were meant to be meditative and contemplative. The purpose of the gospels were to be meditated on. (3.1B)

4. The clothing of the figures is very similar to Roman robes and Greek drapery. However, they are less realistic in these gospels. This is important because that means that the style of the figures are originally pagan, but is being reused for a Christian gospel. (3.1A, 3.1C)

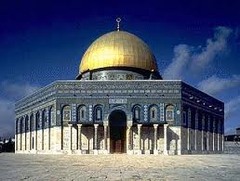

Great Mosque

Córdoba, Spain. Umayyad. c. 785-786 C.E. Stone masonry

1. One of the oldest standing structures from the time period where Muslim's ruled the Iberian Peninsula (Spain, Portugal, and part of France) in the 8th century. (3-1, 3-1a)

2. The site first had a temple that was converted into a church by Visigoths in 572, then a mosque and then completely rebuilt by Umayyad descendants. When Damascus was overtaken by the Abbasids, prince Abd al-Rahman escaped to Spain and created a new capital, Cordoba. He wanted to recreate the grandeur from Damascus and sponsored extensive building programs, etc. that created this great temple. (3-2, 3-2a, 3-2b)

3. The building was expanded over 200 years. The building includes a large hypostyle hall, courtyard with a fountain, garden, covered walkway and a minaret (now encased in a bell tower). It was also made with roman columns (spolia). (3-2b

4. There is a famous mihrab (wall used to identify which direction Mecca is) in the prayer hall. The large archway is decorated with Kufic calligraphy and motifs of plants. Above the mihrab is a dome decorated with gold mosaic. (3-1b)

5. There are double arched columns made with voussoirs of alternating colors. The double arches enhance the interior space which had fairly low ceilings. There is an overall light and airy interior. (3-1b)

Pyxis of al-Mughira

Umayyad. c. 968 C.E. Ivory

- This Pyxis is a cylindrical box that was used for cosmetics. It was kept in a room of a palace and was given a central place as a symbol of the wealth and importance of its owner.

- It was a gift to 18-year old al Mughira (the son of the Caliph) as a coming-of-age present. Ivory objects were bestowed upon members of the Royal family (esp. sons) and were later given to Caliphic allies in hopes they would convert to Islam.

- Ivory allowed for ornate carvings and was also popular during roman times because it was so elegant, smooth, and easily carved.

- The Pyxis is decorated with four eight-loved medallions which are surrounded by figures and animals. One medallion shows lions attacking two bulls. The lions symbolize the victories of the Umayyad. Another medallion shows men on horseback picking dates which represents land under Abbasid control.

- Pyxis were highly portable and the tradition continued into the Byzantine empire and spread to Al-Andalus.

Church of Sainte-Foy

Conques, France. Romanesque Europe. Church: c. 1050-1130 C.E.; Reliuary of Saint Foy: ninth century C.E.; with later additions. Stone (architecture); stone and paint (tympanum); gold, silver, gemstone, and enamel over wood (reliquary)

1. It is an important pilgrimage church, but is also an abbey where monks lived, prayed, and worked. Only parts of the monastery remain, but the church is still almost fully intact. It has barrel vaults and arches on the interior. (3-2B)

2. It is considered a pilgrimage church because of the shape - cruciform plan. This shape was symbolic of the cross and it also helped with large crowds of people. Pilgrims could enter on the west side and then circulate around. (3-2B)

3. The scene of the Last Judgement is depicted on the tympanum. Christ is sitting in the center and right is pointing upward while his left hand is pointing downward. This reminded everyone who was entering about all of the great things of heaven and the horrible things about hell. Many other saints are also depicted on the other sides of Jesus. (3-2C)

4. The reliquary of Sainte-Foy contains the remains of Saint Foy and is one of the most famous throughout Europe. It is covered in gold and different gems. The head stares directly at the viewer and it is thought to have originally been the head of a Roman statue of a child. People come from all over to pay respect to it. (3-2D)

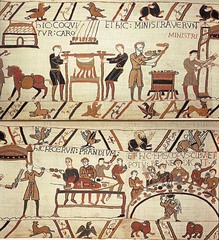

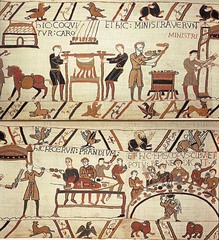

Bayeux Tapestry

Romanesque Europe. c. 1066-1080 C.E. Embroidery on linen

1. The embroidery was commissioned by Bishop Odo, the half-brother of William the Conqueror. It tells the story in Latin of the Battle of Hastings along with William's conquest of England. Essential Knowledge 3-2c.

2. The story is bordered with designs that comment on the main scenes, and others that show scenes of every day life. These upper and lower registers contain fanciful beasts. Essential Knowledge 3-2d.

3. The Bayeux Tapestry has a neutral background and flat figures that are not shown with shadows. There is little evidence of perspective, and color is used in a non-natural manner. Essential Knowledge 3-2c.

4. The narrative tradition goes back to the Column of Trajan. The tapestry has 75 scenes and contains 600 people. Its long plot contributes to the great physical length of the tapestry, 230 feet. Essential Knowledge 3-1c.

Chartres Cathedral

Chartres, France. Gothic Europe. Orignal construction. c. 1145-1115 C.E.; reconstructed c. 1194-1220 C.E. Limestone, stained glass

1. The church was associated with the Virgin Mary. A relic of the tunic of the Virgin Mary was gifted to the church. This tunic was believed to be what she wore when she gave birth to Christ. It was thought to have healing and protecting powers which drew many visitors.

2. The church was burned to the ground, however the tunic remained unharmed. This was a sign to the people to build a new church. Only the Westwork of the previous church survived.

3. The new church was built on the foundation of the previous church. It's design sought to create heaven on earth. The interior is dark, however light from the stained glass windows shines through and reflects off the walls. The light is supposed to represent divinity and is considered to be the least material of god's earthly creations.

4. The gothic elements of the design include ribbed vaults, pointed arches, and flying buttresses.

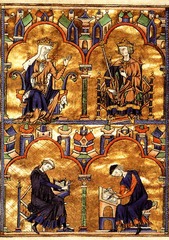

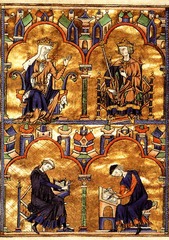

Dedication Page with Blanche of Castle and King Louis IX of France, Scenes from the Apocolypse from Bibles moralisées.

Gothic Europe. c. 1225-1245 C.E. Illuminated manuscript

The Bibles Moralisees were originally commissioned by Blanche of Castile while she was serving as monarch of France

used as the private Bibles of the royal family and thus served a major role in the Biblical and religious education of the future kings.

commissioned in preparation for the marriage of Blanche's son which further highlights their importance to the family, they depict opulence.

Bibles also feature many gothic elements. The figures seen in the illuminated text have long, elongated bodies and necks that were characteristic of the gothic art period.

Lastly, the figures show a move towards greater realism and thus away from many Byzantine conventions.

Röttgen Pietà

Late medieval Europe (Germany). c. 1300-1325 C.E. Painted wood

1. When looking at the Rottgen Pieta you are meant to feel something like terror or distaste. It is meant to intrigue you because that is what Gothic art does. This is very different from previous representations of Christ because in the past he was portrayed as divine and never suffering.

2. This representation of Christ was a shift into showing Jesus suffer the way humans suffer, to make him more like us. Francis of Assisi stressed Jesus' humanity and poverty, like us. Several faith writers talked about Mary holding her dead son and then artists started to catch on.

3. It emphasizes that God understands how we feel and how hard the pain is of being a human. In the Rottgen Pieta you can see that is skin is taut around his ribs to show he led a life of hunger and suffering, like a human.

4. Mary is also traditionally shown as pretty, happy, grateful, wise and older but in Pietas she is shown as grieving and obviously upset about her only sons crucifixion and death which shows her humanity as well.

5. All pietas were devotional images that were intended for contemplation and prayer. Meant to give humans a more personal connection to God because Mary and Jesus are human-like.

Arena (Scrovengni) Chapel, including Lamentation

Padus, Italy. Unknown architect; Giotto di Bonde (artist). Chapel: c. 1303 C.E.; Fresco: c. 1305. Brick (architecture) and fresco

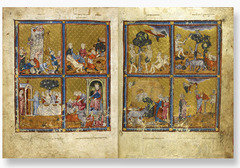

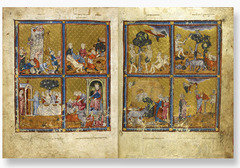

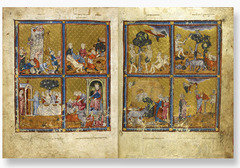

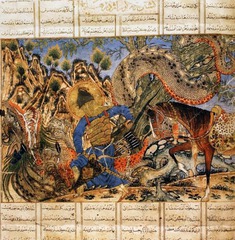

Golden Haggadah (The Plagues of Egypt, Scenes of Liberation, and Preparation for Passover)

Late medieval Spain. c. 1320 C.E. Illuminated manuscript (pigment and gold leaf on vellum)

1. This is an example of medieval Jewish art. At this time, Jewish people were still producing religiously inspired art that also drew influence from the Greco-Roman world and the region's pagan art. At the time of this book's creation, wealthy Jewish patrons would often commission art similarly to Christian elites. (1-4 B).

2. This book tells the story of the book of exodus when the Jewish people fled from Egypt. The book's content meant that it was meant to be read during a Passover ceder meal. (1-4 B).

3. The word Haggadah translates to narration which relates to the book's religious story telling content. The purpose of the book was to fulfill the Jewish requirement to retell the story of the freeing from the slavery of the Egyptians. These books telling this story were mostly kept in the home and as such were more lavish than those in the synagogue. (2-1)

4. The style is French Gothic in the way that it uses space, style of architecture, figure modeling, and general expressions suggest that this book was illustrated by a Christian artist and then a Jewish scribe added the text to the manuscript. The use of a Jewish scribe is reflected in the fact that the book was meant to be read from right to left as most Hebrew texts were. (1-3)

Alhambra

Granada, Spain. Nasrid Dynasty. 1354-1391 C.E. Whitewashed adobe stucco, wood, tile, paint, and gilding

Annunciation Triptych

Workshop of Robert Campin. 1427-1432 C.E. Oil on wood

Pazzi Chapel

Basilicia di Santa Croce. Florence, Italy. Filippo Brunelleschi (architect) c. 1429-1461 C.E.

The Arnolfini Portrait

Jan van Eyck. c. 1434 C.E. Oil on wood

David

Donatello. c. 1440-1460 C.E. Bronze

Palazzo Rucellai

Florence, Italy. Leon Battista Alberti (architect). c. 1450 C.E. Stone, masonry

Madonna and Child with Two Angels

Fra Filippo Lippi. c. 1465 C.E. Tempera on wood

Birth of Venus

Sandro Brotticelli. c. 1484-1486 C.E. Tempera on canvas

Last Supper

Leonardo da Vinci. c. 1494-1498 C.E. Oil and Tempera

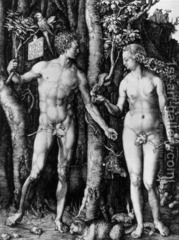

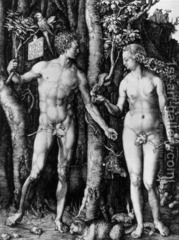

Adam and Eve

Albrecht Dürer. 1504 C.E. Engraving

Sistine Chapel ceiling and altar wall frescoes

Vatican City, Italy. Michelangelo. Ceiling frescoes: c. 1508-1512 C.E.; altar frescoes: c. 1536-1541 C.E. Fresco

School of Athens

Raphael. 1509-1511 C.E. Fresco

Isenheim altarpiece

Matthias Grünewald. c. 1512-1516 C.E. Oil on wood

Entombment of Christ

Jacopo da Pontormo. 1525-1528 C.E. Oil on wood

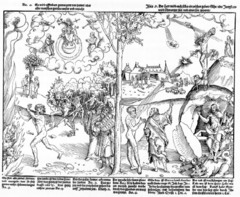

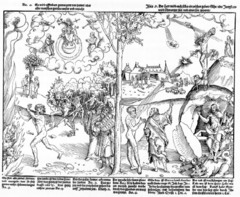

Allegory of Law and Grace

Lucas Cranach the Elder. c. 1530 C.E. Woodcut and letterpress

Venus of Urbino

Titan. c. 1538 C.E. Oil on canvas

Frontispiece of the Codex Mendoza

Viceroyalty of New Spain. c. 1541-1542 C.E. Ink and color on paper

Il Gesù, including Triumph of the Name of Jesus ceiling fresco

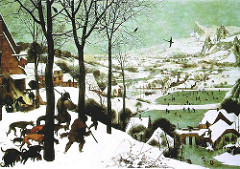

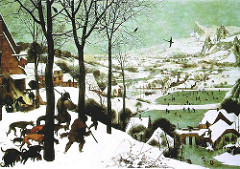

Hunters in the Snow

Pieters Bruegel the Elder. 1565 C.E. Oil on woods

Mosque of Selim II

Edrine, Turkey. Sinan (architect), 1568-1575 C.E. Brick and stone

Calling of Saint Matthew

Caravaggio. c. 1597-1601 C.E. Oil on canvas

Henri IV Recieves the portrait of Marie de' Medici, from the Marie de' Medici Cycle

Peter Paul Rubens. 1621-1625 C.E. Oil on canvas

Self-Portrait with Saskia

Rembrandt van Rijn. 1636 C.E. Etching

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

Rome, Italy. Francesco Borromini (architect) 1638-1646 C.E. Stone and stucco

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa

Cornaro Chapel, Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria Rome, Italy. Gian Lorenzo Bernini. c. 1647-1652 C.E. Marble (sculpture); stucco and gilt bronze (chapel)

Angel with Arquebus, Asiel Timor Dei

Master of Calamarca (La Paz School). c. 17th century C.E. Oil on canvas

Las Meninas

Diego Velázquez. c. 1656 C.E. Oil on canvas

Women Holding a Balance

Johnnes Vermer. c. 1664 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Palace of Versailles

Versailles, France. Loius Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart (architects). Begun 1669 C.E. Masonry, stone, wood, iron, and gold leaf (architecture); marble and bronze (sculpture); gardens

1. The work was designed for Louis XIV at Versailles as a way to consolidate his power by forcing the French nobility off their estates to live there at least half the year. The lavish lifestyle the king lived there was meant to bankrupt the nobility who tried to emulate it in order to maintain their status, putting them at the mercy of the king's patronage. (3-5C)

2. The palace itself was designed in a grand classical style, with Doric entablatures and columns and severe symmetry, to emphasize the rationality, order and imperial power that Louis brought to France, rivaling that of Roman emperors. Art in the palace followed the model of Le Brun in emphasizing classical yet dramatic and allegorical works that forced the viewer to encounter the power and glory of Louis as a demi-god-like Sun King. Le Brun also founded the French Academy of Arts under Louis to centralize artistic production and promote the king's classical aesthetic; it became the dominant art academy of Europe. (3-4; 3-4B)

3. The main space in the palace was the Hall of Mirrors, with the Salon of Peace for domestic affairs and the Salon of War for foreign policy at each end. Besides being heavily gilded, the decoration features ceiling paintings by Le Brun allegorically celebrating Louis' achievements and large windows facing the garden with large mirrors on the opposite wall. The mirrors reflected light off all the other surfaces, emphasizing the radiance of Louis' reign as the Sun King, the king around whom all other beings and bodies orbited. (3-4, 3-4C)

4. The gardens nearby the palace were designed in elaborate patterns of geometric symmetry by Le Notre to emphasize Louis's control even over the elements of nature. Orange trees and other plantings from distant lands spoke to the king's control of a vast colonial empire in N. America and elsewhere, which helped finance the creation of the complex. (3-4C, 3-3B)

5. While the landscape relaxed into a more picturesque and irregular pattern further from the palace (and the water features there were only turned on when the king processed through), artificial grottoes depicting Louis as Apollo the classical sun god confronted inhabitants who wandered the grounds, and all avenues eventually converged back in the palace on Louis bedroom, where each day the public ceremonies of his ritually rising and going to sleep attested to his central importance. (3-4, 3-4B)

Screen with the Siege of Belgrade and hunting scene

Circle of the González Family. c. 1697-1701 C.E. Tempera and resin on wood, shell inlay

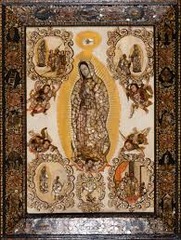

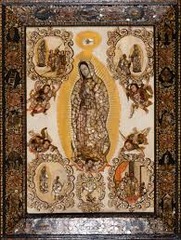

The Virgin of Guadalupe

Miguel González. c. 1698 C.E. Based on original Virgin of Gaudalupe. Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City. 16th century C.E. Oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl

Fruit and Insects

Rachel Ruysch. 1711 C.E. Oil on wood

Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo

Attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez. c. 1715 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Tête à Tête, from Marriage à la Mode

William Hogarth. c. 1743 C.E. Oil on canvas

Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Miguel Cabrera. c. 1750 C.E. Oil on canvas.

A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on the Orrery

Joseph Wright of Derby. c. 1763-1765 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Swing

Jean-Honoré Fragonard. 1767 C.E. Oil on canvas

Monticello

Virginia, U.S. Thomas Jefferson (architect). 1768-1809 C.E. Brick, glass, stone, and wood

The Oath of the Horatii

Jacques-Louis David. 1784 C.E. Oil on canvas.

George Washington

Jean-Antoine Hudson. 1788-1792 C.E. Marble

Self-Portrait

Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. 1790 C.E. Oil on canvas

Y no hai remedio, fromo Los Desastres de la Guerra, plate 15

Francisco de Goya. 1810-1823 C.E. (publised 1863) Etching, drypoint, burin, and burnishing

La Grande Odalisque

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. 1814 C.E. Oil on canvas

Liberty Leading the people

Eugène Delacroix. 1830 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Oxbow

Thomas Cole. 1836 C.E. Oil on canvas

Still Life in Studio

Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre. 1837 C.E. Daguerreotype.

Slave Ship

Joseph Mallord William Turner. 1840 C.E. Oil on canvas

Palace of Westminster

London, England. Charles Barry and Augustus W. N. Pugin (architects). 1840-1870 C.E. Limestone masonry and glass

The Stone Breakers

Gustave Courbet. 1849 C.E. (destroyed in 1945). Oil canvas

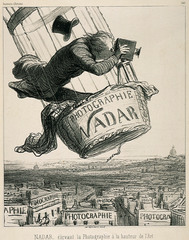

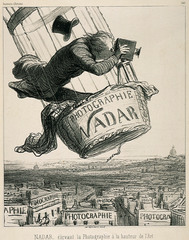

Nadar Raising Photography to the Height of Art

Honoré Daumier. 1862 C.E. Lithograph

Olympia

Édouard Manet. 1863 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Saint-Lazare Station

Claude Monet. 1877 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Horse in Motion

Eadweard Muybridge. 1878 C.E. Albumen print

The Valley of Mexico from the Hillside of Santa Isabel

José María Velasco. 1882 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Burghers of Calais

Auguste Rodin. 1884-1895 C.E. Bronze

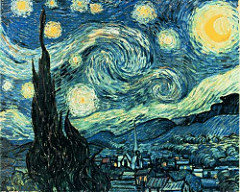

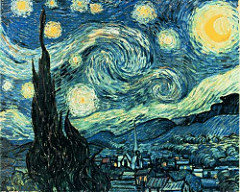

The Starry Night

Vincent van Gogh. 1889. Oil on canvas

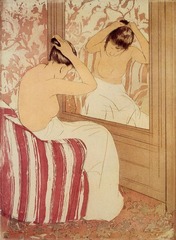

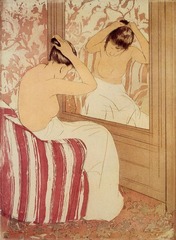

The Coiffure

Mary Cassatt. 1890-1891 C.E, Drypoint and aquatint